06 December 2011

20 November 2011

Fathers and Sons condensed

A fat cock with variegated plumage walks gravely up and down, striking the steps with the spurs on his big yellow feet; a cat, all covered with ashes, looks at him with rather an unfriendly air from the top of the balustrade where it is crouching. The sun burns hot; from the low chamber that serves as the entry to the inn issues a smell of freshly-cooked rye bread. A fat pigeon lights on the road and runs hastily to drink in a puddle of water near the well. Several carts, whose horses are unbridled,* rapidly go over a narrow cross-road; each carries one or two peasants in unbuttoned tulupes. A vast cultivated plain extends to the horizon, and the soil rises slightly, to fall soon after. Some little woods appear at rare intervals, and ravines, curtained with scattered low bushes, wind around a little further, recalling with some faithfulness the drawings that represent them on the old maps dating from the reign of the Empress Catharine. From time to time are seen little brooks with bare banks, ponds kept in by bad dikes; poor villages, whose low houses are surmounted by black thatched roofs, half off; miserable barns, with walls formed of interwoven branches, with enormous doors gaping on empty spaces; churches, some of brick, covered with a layer of plaster that is beginning to come off, others of wood, topped by a badly supported cross, and surrounded with ill-kept graveyards. All the peasants have a wretched air, and ride little worn-out horses; the willows that edge the road,** with their torn bark and their broken branches, resemble beggars in rags; shaggy cows, lean and fierce, eagerly browse on the herbage along the ditches. All grows green, all moves gently, and sparkles with a gilded splendor under the mild breath of a warm and light wind -- trees, bushes, and grass. From all sides rise the interminable trills of the larks; the lapwings cry as they hover over the damp meadows, or run silently over the clods of ground; crows whose black plumage contrasts with the tender green of the still short wheat, are seen here and there; they are distinguished with more difficulty in the midst of the rye that has already begun to whiten; their heads hardly rise for a moment above this waving sea. A lighted samovar*** waits on a table set between large bushes of lilac. The day is rapidly declining; the sun is hid behind a little aspen wood situated half a verst from the garden, and casts an endless shadow on the moveless fields. A peasant mounted on a white horse trots along a narrow path which skirts the wood; although he is in shadow, his whole person is distinctly seen, and a patch on his shoulder is even noticeable; the horse’s feet move with a regularity and a cleanness that is pleasing to the eye. The rays of the sun penetrate into the wood, and, traversing the thicket, colour the trunks of the aspens with a warm tint which gives them the appearance of savin trunks, while their almost blue foliage is surrounded by a pale sky, slightly reddened by the evening twilight. The swallows are flying very high; the wind has entirely ceased; belated bees feebly buzz in the lilac flowes; a swarm of gnats dances above an isolated branch that stands out into the air. The soft and warm night appears with its almost black sky, accompanied by the feeble murmur of the trees and the healthy odor of a free and pure air. A table of heavy wood, covered with papers so black with dust that they look as if smoked, occupies the space between two windows; on the walls hang Turkish guns, nagaïkas,**** a sabre, two large maps, anatomical drawings, the portrait of Hufeland, a crown made of hair, placed in a black frame, and a diploma, likewise under glass; between two enormous closet bookcases of birch root is a leathern divan, well rubbed and torn in several places; books, little boxes, stuffed birds, vials and retorts are placed pell-mell on the shelves; in one corner of the room is a worn-out electrical machine. A little room exhales an odor of fresh shavings, and two crickets behind the stove sing sleepily. It is mid-day. The heat is stifling, in spite of the fine curtain of white clouds which veils the sun. Everything is silent; the cocks alone crow in the village, and their languid voices give all who hear them a singular sensation of laziness and ennui. From time to time the piercing cry of a young sparrow-hawk comes like a plaintive appeal from the top of a tree. The morning is magnificent, and fresher than the preceding days. Little mottled clouds pass in flakes over the pale azure of the sky; a fine dew covers the leaves of the trees, and the spiders’ webs shine like silver on the grass; the damp, dark ground seems still to keep some traces of the first flush of the day; the song of the larks comes down from all parts of the sky. A finch sings its ceaseless song in the foliage of a birch. A puff of wind disturbs the leaves and carries away the words. Everything in the house seems in some way to be darkened; every face is lengthened; a strange silence reigns, even in the yard; they have sent off to the village a crowing cock, who must have been remarkably surprised by such a proceeding. Winter has come; winter with the terrible silence of its frosts, the compact and creaking snow, the rosy rime on the branches of the trees, the pillars of thick smoke above the chimneys showing against a sky pale blue and cloudless, the eddies of warm air shooting out of opened doors, the fresh and nipped-looking faces of the passers-by, and the hasty trot of horses half-frozen by the cold. A January day is drawing near its end; the coldness of the evening condenses still more the motionless air, and the blood-coloured twilight is rapidly extinguished.

* A strange custom of the Russian peasant.

** In accordance with a ukase of the Emperor Alexander I., all the high roads in Russia are planted with willows.

*** A large vessel in which tea is made.

**** Cossack whips

14 October 2011

Les défauts de l'esprit

09 October 2011

Ô humanité! Ô turpitude!

05 October 2011

cette vieille canaillerie immuable et inébranlable

04 October 2011

le cimetière oriental

three exclamations

Don your mask, Sokolov, that your anaerobic fermentations may set the tubas of your fame blaring and that your irrepressible flatus may transform abscissae and ordinates into sublime anamorphoses!

[...]

Vente, Sokolov, sur ce monde luxueux et dérisoire, et quand dans ces miroirs brisés par tes tracés se dessinent en surimpression les nymphettes se refaisant les lèvres, que ton ubiquité soit le reflet multiplié des vices de la terre. Ô Sokolov, ton hyperacousie fait sursauter ta main. Regarde aux hublots de ton masque embués par ta fièvre paludéenne et créatrice se dessiner épures et graphiques tandis qu'oscilloscopes cathodiques et vu-mètres vascillent, serpentent et fluorescent sur les atonalités de Berg et Schönberg dont le dodécaphonisme s'allie à tes gaz contrapuntiques!

Flatulate, Sokolov, at this opulent and derisory world, and when in these mirrors shattered by your skidmarks there coalesces an overlay of nymphettes redoing their lips, may your ubiquity be the multiplied reflection of the world's vices. O, Sokolov, your hyperacousia causes your hand to flinch. Peer through the goggles of your gas mask misted by your malarial and creative fever to draw preliminary sketches and diagrams while the cathodic oscilloscopes and VU meters flicker, snake and glow to the atonalities of Berg and Schönberg whose twelve-tones combine with your contrapuntal gases!

[...]

Tu as vécu Sokolov, me disais-je en inhalant mes gaz, tu as vécu ton inavouable destin. Mais que craindrais-tu de la mort, toi qui ne fus ta vie durant que ferments et putréfactions, signalés, codifiés, séismographiés à jamais par ta main prophetique!

You have lived, Sokolov, I said to myself as I inhaled my own gas, you have lived out your shameful destiny. But why should you fear death, you whose whole life was nothing but ferment and putrefaction, revealed, codified and seismographed by none other than your own prophetic hand!

02 September 2011

Hypnos

30 August 2011

L’incommensurable goujaterie

C’était le grand bagne de l’Amérique transporté sur notre continent ; c’était enfin, l’immense, la profonde, l’incommensurable goujaterie du financier et du parvenu, rayonnant, tel qu’un abject soleil, sur la ville idolâtre qui éjaculait, à plat ventre, d’impurs cantiques devant le tabernacle impie des banques !

Eh ! croule donc, société ! meurs donc, vieux monde ! s’écria des Esseintes, indigné par l’ignominie du spectacle qu’il évoquait ; ce cri rompit le cauchemar qui l’opprimait

Ah ! fit-il, dire que tout cela n’est pas un rêve ! dire que je vais rentrer dans la turpide et servile cohue du siècle ! Il appelait à l’aide pour se cicatriser, les consolantes maximes de Schopenhauer ; il se répétait le douloureux axiome de Pascal : « L’âme ne voit rien qui ne l’afflige quand elle y pense », mais les mots résonnaient, dans son esprit comme des sons privés de sens ; son ennui les désagrégeait, leur ôtait toute signification, toute vertu sédative, toute vigueur effective et douce.

Il s’apercevait enfin que les raisonnements du pessimisme étaient impuissants à le soulager, que l’impossible croyance en une vie future serait seule apaisante.

13 July 2011

The Days of the King

Interview with author Filip Florian

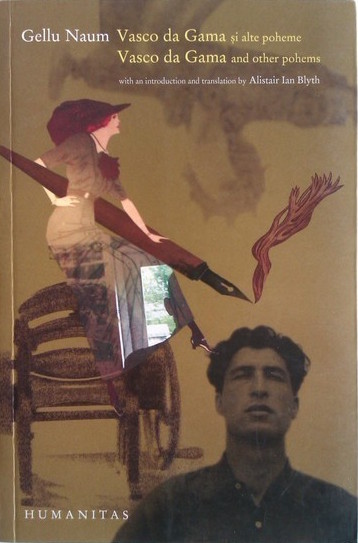

Interview with translator Alistair Ian Blyth

.

11 July 2011

The cockroach in Russian literature (3): Gogol (3)

08 July 2011

The Cockroach in Russian Literature (2): Gogol (2)

Огромный, величиною почти с слона, таракан остановился у дверей и просунул свои усы.

See also: The Cockroach in Russian Literature (1): Gogol (1)

26 May 2011

Gogolian piles (4)

If only you knew how sorry I was to find not you but rather the note you left on my desk. Had I returned but a minute earlier, I might still have been able to see you in person. The other day I wished to pay you a visit without fail, but it was as if everything conspired to thwart me: a cold got it into its head to conjoin itself to my haemorrhoidal virtues and so now I have an entire horse collar of kerchiefs around my neck. It looks like this illness will sequester me for the week. Nevertheless, I have decided not to sit around idling and instead of verbal presentations to sketch out my thoughts and teaching plan on paper.

Если бы вы знали, как я жалел, что застал вместо вас одну записку вашу на моем столе. Минутой мне бы возвратиться раньше, и я бы увидел вас еще у себя. На другой жедень я хотел непременно побывать у вас; но как будто нарочно все сговорилось идти мне наперекор: к моим геморроидальным добродетелям вздумала еще присоединиться простуда, и у меня теперь на шее целый хомут платков. По всему видно, что эта болезнь запрет меня на неделю. Я решился, однако ж, не зевать и вместо словесных представлений набросать мои мысли и план преподавания на бумагу.

Gogolian piles (3)

"Cat's mint" (i.e. catsfoot). Glechoma hedera terrestris, alleviates piles.

Gogolian piles (2)

Having ordered a very light supper, which consisted of only a sucking pig, Chichikov

Потребовавши самый легкий ужин, состоявший только в поросенке, <Чичиков> тот же час разделся и, забравшись под одеяло, заснул сильно, крепко, заснул чудным образом, как спят одни только те счастливцы, которые не ведают ни геморроя, ни блох, ни слишком сильных умственных способностей.

25 May 2011

Gogolian piles (1)

"Would you like to take some snuff? It chases away headaches and gloomy moods; it is even good for treating haemorrhoids."

Saying this, the clerk offered Kovalev his snuffbox, rather deftly flipping up the lid, which had a portrait of some lady in a hat.

This thoughtless behaviour exceeded the limits of Kovalev's patience.

"How you find it appropriate to joke about it I do not know," he said indignantly. "Can't you see I do not have the wherewithal to take snuff?"

- Не угодно ли вам понюхать табачку? это разбивает головные боли и печальные расположения; даже в отношении к геморроидам это хорошо.

Говоря это, чиновник поднес Ковалеву табакерку, довольно ловко подвернув под нее крышку с портретом какой-то дамы в шляпе.

Этот неумышленный поступок вывел из терпения Ковалева.

- Я не понимаю, как вы находите место шуткам, - сказал он с сердцем, - разве вы не видите, что у меня именно нет того, чем бы я мог понюхать?

17 May 2011

исполинский образ скуки

Хотя бы только пожелать так, хотя бы только насильно заставить себя это сделать, ухватиться бы за этот <день>, как утопающий хватается за доску! Бог весть, может быть, за одно это желанье уже готова сброситься с небес нам лестница и протянуться рука, помогающая возлететь по ней.

Но и одного дня не хочет провести так человек девятнадцатого века! И непонятной тоской уже загорелася земля; черствей и черствей становится жизнь; всё мельчает и мелеет, и возрастает только в виду всех один исполинский образ скуки, достигая с каждым днем неизмеримейшего роста. Всё глухо, могила повсюду. Боже! пусто и страшно становится в твоем мире!

Собрания сочинений Гоголя, Полное собрание сочинений в 14 томах (1937—1952), Том восьмой: Статьи, Выбранные места из переписки с друзьями, Светлое воскресенье, стр. 416

If only one might so desire, if only one might force oneself to do it, to clutch at this [day], like a drowning man clutches at a plank! God knows, perhaps for this desire alone a ladder is ready to drop down to us from the heavens and a hand is ready to extend to us, helping us to soar up it.

But the man of the nineteenth century does not wish to spend even one day like this! And with an incomprehensible anguish the earth is already burning; life is becoming ever more callous; everything is becoming pettier and shallower, and before all our eyes only the single gigantic image of boredom rears up, and with every passing day it attains an immeasurable height. All is dull, everywhere the tomb. O, God! it grows desolate and terrible in Your world!

Gogol, Selected Passages from the Correspondence with Friends (1847), Holy Sunday

15 May 2011

The proscenium of eternity

Letters, ed. Raymond Lister. Oxford, 1974. Vol. 1, p. 50

18 April 2011

Сон и Явь

глава из книги Якова Семеновича Друскина (1902-1980)

Сон и Явь, 1968

Daniil Ivanovich used to say: it is necessary to go up to the abyss, to stand on its very edge, to look down and not to fall.

23 February 2011

Before Brezhnev Died

Before Brezhnev Died by Iulian Ciocan is a dense, multi-layered novel of everyday life in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Moldova, a land at the periphery of both the USSR and the communist Eastern Bloc. It is a novel that is in many ways different to the more subjective “autobiographical fictions” of the communist past which have been published by Romanian writers from the western side of the Prut in recent years.

The novel consists of ten chapters: nine interlocking short stories and a penultimate meta-chapter that explores the book’s methods and technique. In this explanatory chapter, entitled “An Elucidation”, Iulian Ciocan tries to answer the question put to him by an indignant older writer, who is working on a novel of post-Soviet, transition-period Moldova: “Why do you keep raking up the Soviet past? How much longer are you going to be its prisoner?” This reinvented writer of the old guard, who has “liberated himself from the tyranny of the Soviet past”, suspects Ciocan of trying somehow to revive “socialist realism”. However, socialist realism and the reality of socialism are two very different things. The “reality” of the Soviet period, in the sense of everyday life during that time, is still largely unexplored territory. The stories of the Gulag and the Terror are well known, but less has been written about the real life behind the “absurd, grotesque, sometimes comical” ideological façade created by socialist realism as propaganda for both foreign and domestic consumption. Of course, post-Soviet writers such as Victor Erofeev, Vladimir Sorokin and Ludmila Ulitskaya have described everyday Soviet life in their different ways. But Soviet reality was not only a Russian reality. The USSR was by no means the monolithic entity it is sometimes imagined to be. As Iulian Ciocan points out, “there was not a single Soviet everyday, one that was the same for a Russian, a Moldovan and a Tungus, for the centre and the periphery.” Moreover, the reality of Soviet Moldova itself, “the Latin periphery of the Empire,” was by no means homogenous; that reality was more complex than the perspective to be found in a Ludmila Ulitskaya novel, for instance, where Moldovans are merely men with “droopy moustaches” who dump mounds of rubbish on the coast of the Black Sea.

The characters in the novel, whose lives can be seen to intersect in dramatic and unexpected ways in each chapter, range from Grișa Furdui, a lowly collective farm worker, to Pavel Fiodorovici Kavrig, a highly placed Party apparatchik. In between there are factory workers, war veterans, pensioners, schoolteachers, hooligans, and the seemingly model communist pioneer Iulian, a semi-autobiographical portrait of the author. Ciocan consciously rejects subjectivity as a narrative technique, however, preferring to make use of multiple perspectives, which allow the same event to be simultaneously comic and tragic, absurd and amusing, depending on the viewpoint of the particular character. Reality shifts according to the perspective of the protagonist of each individual chapter. For example, in one chapter we are introduced to Ion Pîslari, a factory worker who lives with his wife and child in the grotesque squalor of a cramped communal apartment block. In the next chapter, these soul-destroying conditions seem like a veritable paradise on earth to Pîslari’s cousin, Grișa Furdui, who is visiting Kishinev from the country, where he leads an even more dehumanising life of grinding toil on a state collective farm. His “nostrils anaesthetised by rural dung,” Grișa avidly inhales the “comforting reek of boiled onion/borsht/urine/bleach” that pervades the building of his more fortunate city cousin. Even the filthy communal toilets, with the sounds of someone straining in the next cubicle, are “a revelation” after his native village and the “rudimentary back-yard pit where you freeze your arse off in winter”. To cynical city folk, Grișa Furdui is the incarnation of “bucolic ignorance”, a “messenger of rural eternity.” On the other hand, the culture shock of seeing the city for the first time convinces Grișa that the utopia of communist propaganda really does exist. It also makes him realise that his fellow peasants, or rather collective farm workers, are “sleepwalkers”, reduced to a mindless, vegetative existence by never-ending toil and abject poverty. Again, this bleak picture of rural life contrasts with the official socialist reality, which is presented in the following chapter in the form of inserts within the narrative, culled from the voiceover to an idyllic episode of Po zayavkam rabotnikov zhitonovodstva (At the Requests of the Animal Husbandry Workers) about Stakhanovite cow-milker Frasîna Paierele.

Throughout the novel, there are other similar inserts, drawn from Soviet-era propaganda and providing striking, even disorienting contrasts with the squalid reality of the characters’ everyday lives. The effect of these diametrically opposed discourses and shifting perspectives is one of defamiliarisation or estrangement—the ostranenie theorised by Victor Shklovsky. Indeed, as a fictional approach to the Soviet period, Ciocan recommends Shklovsky’s method in the chapter “An Elucidation”, rather than falling prey to maudlin self-pity about the hardships and horrors of the past. Ultimately, it is better to bring out the comical, bizarre or absurd side of events, because in any case the glut of human tragedies on the nightly television news bulletin has wholly numbed us to horrors.

The grotesquely absurd, random violence of some events in the novel is reminiscent of Daniil Kharms’ sluchai or “accidents”. For example, pensioner Dochia Barbalat is crushed by a falling crane as she returns home from the market with laden bags. Her husband, Nicolae Barbalat, encounters utter indifference, mockery and even aggression on the part of the authorities when he tries to seek justice. In another chapter, widower and war veteran Polikarp Feofanovici is hit on the head by a rotten tomato, thrown from the roof by a communist pioneer, quite possibly the young Iulian himself. The event provokes an existential crisis, forcing him to confront, in disbelief, the degeneration of Soviet society and morals, the ineluctable failure, lies, poverty and decay of the system itself. This decay was embodied in the person and crepuscular rule of Leonid Brezhnev. For Iulian, the death of Brezhnev—itself played out amid the initial denials of a system for which lying was a reflex, and then amid the grotesque, tragicomic rituals of insincere mourning—finally shatters the illusion of Soviet invulnerability and perpetuity.

Before Brezhnev Died is unsettling and hilarious by turns. It is a novel that provides a unique and unfamiliar—for readers outside the Republic of Moldova, and even for readers in Romania, with their own different experiences of everyday life under communism—perspective on the former Soviet Union.

20 February 2011

The Beckett Bowel Books

I replied, dear agente provocatrice, that I would not have a finger laid on the section entitled Amor intellectualis etc., nor on the Thema Coeli, nor on Endon's Affence, nor on the last will and fundament, but that so far as the rest was concerned I would willingly remove all ties and supports, dripstones, keystones, cornerstones, buttresses, and, with especial pleasure, the entire foundations, and accept full and entire responsibility for the ensuing detritus. The owls, cats, foxes and toads of the higher criticism could be relied on to complete the picture, a romantic one. ...

(1) The at the time unpublished novel Murphy

06 February 2011

The ruins of Babel

17 January 2011

British grossièreté

“To horse-race, fair, or hoppin go,

There play our cast among the whipsters,

Throw for the hammer, lowp (leap) for slippers,

And see the maids dance for the ring,

Or any other pleasant thing;

Fart for the pigg, lye for the whetstone,

Or chuse what side to lay our betts on.”

We find notes explaining the word “Hoppin” by “annual feasts in country towns where no market is kept,” and “lying for the whetstone,” I’m told, has been practised, but farting for the pigg is beyong the memory of any I met with; tho’ it is a common phrase in the north to any that’s gifted that way; and probably there has been such a mad practice formerly. -- The ancient grossièreté of our manners would almost exceed belief. In the stage directions to old Moralities (1) we often find “Here Satan letteth a fart.”

(1) I.e. morality plays